Central Nervous System Infections

- related: ID

- tags: #id

Meningitis

A positive Gram stain result for bacteria or yeast is seen in only 5% of patients with community-acquired meningitis. Meningitis with a negative Gram stain result is a diagnostic and management challenge because the differential diagnosis includes urgent treatable causes, such as bacterial or fungal meningitis. Bacterial cultures of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or blood are needed for antimicrobial sensitivity studies in suspected bacterial meningitis, but results are insufficiently timely to differentiate bacterial from viral meningitis. In situations of clinical uncertainty, rapid diagnostic techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for common viruses and arboviral serologies can reduce use of clinically unhelpful cranial imaging, hospitalization, and antimicrobial therapy.

Viral Meningitis

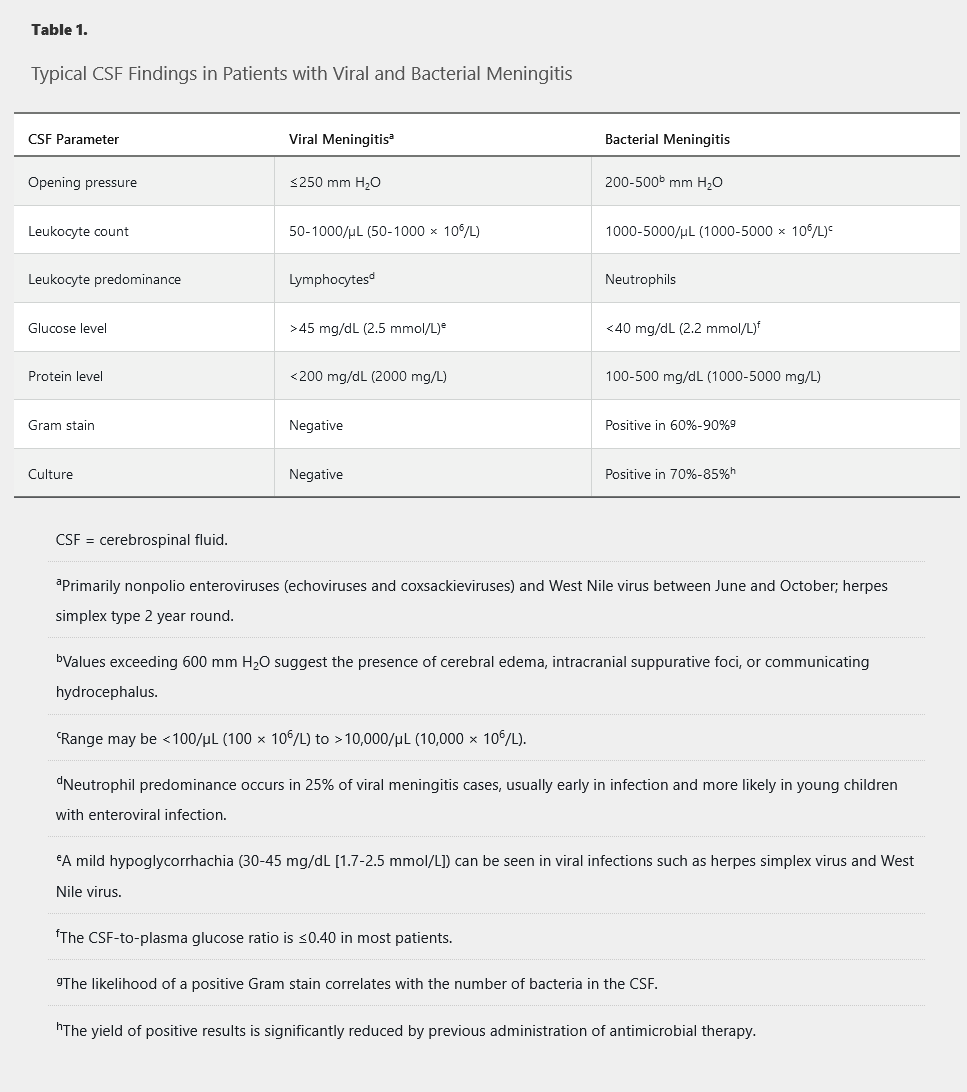

Enteroviruses are the most common cause of viral meningitis, usually presenting between May and November in the Western Hemisphere, with symptoms including headache, fever, nuchal rigidity, photophobia, nausea, vomiting, myalgias, pharyngitis, maculopapular rash, and cough. Lymphocytic pleocytosis of the CSF with a normal glucose level and mildly elevated protein level is typical (Table 1). The diagnosis is confirmed by enterovirus PCR. Treatment is supportive with a benign clinical course.

Herpesviruses can cause meningitis year round and include herpes simplex virus (HSV) types 1 and 2, varicella-zoster virus (VZV), cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, and human herpesvirus 6. Of the herpesviruses, HSV-2 is the most common cause of viral meningitis that can sometimes recur (recurrent benign lymphocytic meningitis, also called Mollaret meningitis). The CSF findings resemble enteroviral meningitis. Outcomes for HSV-2 meningitis are generally favorable without the need for acyclovir therapy.

VZV can cause encephalitis, aseptic meningitis, myelitis, and a vasculitis presenting as a stroke. Vesicular lesions are a clue to the diagnosis but may be absent (zoster sine herpete). VZV encephalitis and vasculitis may present with a hemorrhagic CSF. VZV may be present in the CSF without meningitis or encephalitis, and patients with primary varicella or zoster do not require lumbar puncture unless they have clinical signs of central nervous system (CNS) involvement. Immunocompromised and older adult patients are at higher risk of VZV meningitis and encephalitis. The diagnosis is confirmed by VZV PCR of the CSF, and therapy is parenteral acyclovir.

Mosquito-borne viruses such as West Nile virus (WNV), St. Louis encephalitis, and California encephalitis can cause meningitis or encephalitis between June and October in the Western Hemisphere. Neuroinvasive WNV may present with acute flaccid paralysis, which may lead to persistent weakness or death. The CSF formula resembles enteroviral meningitis. The diagnosis is made by serum or CSF serology (WNV IgM); WNV PCR of the CSF is insensitive. Treatment is supportive.

Acute HIV infection can present as aseptic meningitis associated with a mononucleosis-like syndrome with fever, rash, and myalgias.

Less common viral causes include mumps, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, parainfluenza, adenoviruses, influenza A and B, measles, rubella, poliovirus, rotavirus, and parvovirus B19.

Bacterial Meningitis

Bacterial meningitis usually presents with acute meningeal signs (fever, nuchal rigidity) and altered mental status. Since the introduction of conjugate vaccines, Haemophilus influenzae and Neisseria meningitides meningitis incidence has decreased, making Streptococcus pneumoniae the most common cause of community-acquired bacterial meningitis. N. meningitides serogroup B accounts for 40% of infections in the United States because the quadrivalent conjugate vaccine (ACYW-135) does not include serogroup B. Two FDA-approved vaccines that target serogroup B are available in the United States. Streptococcus agalactiae is now the third most common cause of bacterial meningitis in adults. Listeria monocytogenes is an uncommon cause of meningitis in adults; however, the risk increases in older adults and those with altered cell-mediated immunity.

Bacterial endocarditis caused by S. pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus can present as purulent meningitis. Clinical clues include a history of valvular disease, a new regurgitant murmur, embolic phenomena, or other stigmata of endocarditis. Injection drug use and hemodialysis are risk factors for S. aureus, and alcoholism is a risk factor for S. pneumoniae endocarditis. Patients may also present with stroke symptoms secondary to embolic infarction.

Lyme disease, caused by Borrelia burgdorferi, can present with a lymphocytic meningitis approximately 2 to 10 weeks after development of erythema migrans. Common clinical features include headache, photophobia, nausea, history of erythema migrans, tick bite in an endemic area, and facial paralysis, which can be unilateral or bilateral. Because the CSF formula resembles enteroviral meningitis, the “rule of 7s” was derived and validated to accurately classify a patient at low risk of having Lyme disease (headache duration <7 days, <70% CSF mononuclear cells, and absence of a seventh facial nerve palsy). Lyme meningitis usually occurs in the summer and fall.

Treponema pallidum meningitis can occur in the secondary or tertiary phase of syphilis. Headache and meningismus are common, and the CSF usually shows a lymphocytic pleocytosis with an elevated protein level. In tertiary syphilis, neurosyphilis can be asymptomatic or symptomatic. Symptomatic neurosyphilis can present with primarily meningovascular (stroke presentation) or parenchymatous (tabes dorsalis, general paresis) features.

Leptospiral meningitis develops in the immune or second phase of the illness and is classically associated with uveitis, rash, conjunctival suffusion, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly. The CSF formula resembles enteroviral meningitis, and the diagnosis is established by CSF or urine culture or by serology.

Evaluation

All patients with suspected meningitis should undergo lumbar puncture. CSF findings characteristic of bacterial meningitis are provided in Table 1. A negative CSF Gram stain result is more common in patients with previous antibiotic therapy or in patients with L. monocytogenes or gram-negative bacilli (sensitivity <50%) infections. CSF latex agglutination tests for detecting bacterial antigens are no longer recommended because of low sensitivity (70%) and specificity, although they may play a role in patients with previous antibiotic therapy or culture-negative meningitis. Multiplex PCR assay for detection of S. pneumoniae, N. meningitidis, H. influenzae, and L. monocytogenes has high sensitivity (100%) and specificity (98%) and is increasingly available. If a head CT is indicated before lumbar puncture (focal neurologic findings, altered mental status, papilledema, new seizure, history of CNS disease, or immunocompromise), imaging should not delay empiric antibiotic therapy, which should be started after promptly obtaining blood cultures. See Figure 1 for management of suspected bacterial meningitis.

Management

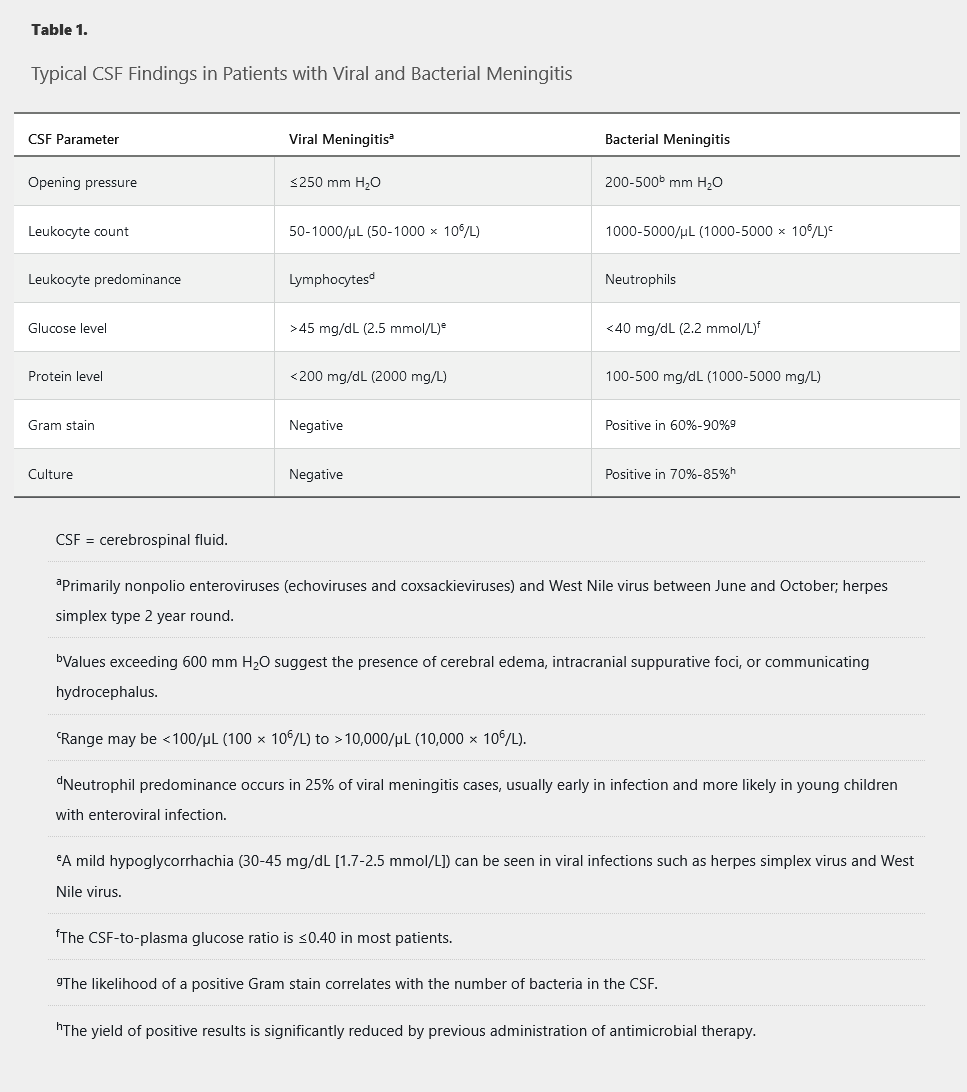

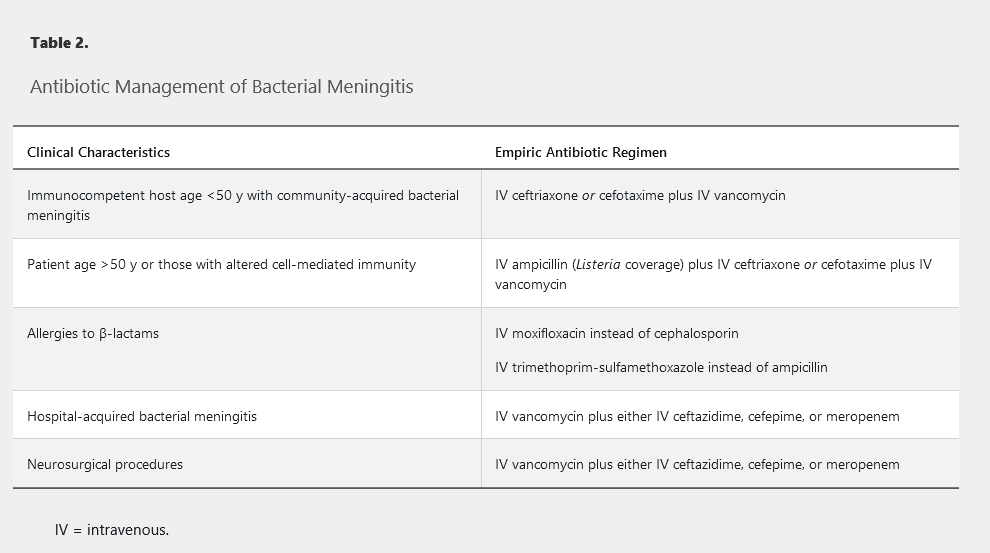

Intravenous antibiotic therapy should be started as soon as possible. If the CSF Gram stain result is negative, initial empiric antibiotic selection is based on age, local epidemiologic patterns of pneumococcal resistance, and the necessity for ampicillin coverage for L. monocytogenes (Table 2). Despite antibiotic therapy, mortality for bacterial meningitis remains approximately 25%. Adjunctive dexamethasone (10 mg every 6 hours for 4 days) reduces morbidity and mortality in adults with pneumococcal meningitis and reduces the risk of neurologic sequelae in bacterial meningitis in developed countries; it should be given concomitantly with the first dose of antibiotic therapy.

Subacute and Chronic Meningitis

Subacute and chronic meningitis are defined by symptom duration between 5 and 30 days and more than 30 days, respectively. The most common infectious causes are Mycobacterium tuberculosis and fungi.

Tuberculous Meningitis

Mycobacterial tuberculosis meningitis classically presents as basilar meningitis with cranial neuropathies (particularly of cranial nerve VI), mental status changes, and the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone. A history of tuberculosis exposure, an abnormal chest radiograph, a positive tuberculin skin test result, and a positive interferon-γ release assay result are suggestive but can be absent. CSF examination shows a lymphocytic pleocytosis (leukocyte count of 100-500/µL, 100-500 × 106/L), elevated protein level, and hypoglycorrhachia (glucose levels < 45mg/dL). CSF acid-fast bacilli smear is insensitive, and culture results are positive in only 38% to 88% of patients. Culture sensitivity increases when lumbar punctures are performed serially for at least 3 days. Nucleic acid amplification testing should be performed when possible, especially when the acid-fast bacilli stain result is negative and suspicion is high, because it might increase diagnostic yield. Antituberculous therapy (4 drug combo) should be administered for 1 year, and adjunctive glucocorticoids should be given initially because of their association with improved outcomes.

1.Tuberculosis and fungal infection are the most common causes of chronic meningitis.

Fungal Meningitis

Fungal pathogens, including Cryptococcus neoformans, Coccidioides immitis, Histoplasma capsulatum, and endemic mycoses, are a significant cause of subacute or chronic meningitis syndromes. Fungal meningitis is discussed in the Fungal Infections chapter.

Neurobrucellosis

Neurobrucellosis occurs in 4% to 11% of patients with brucellosis, which is endemic to countries in the Mediterranean, Middle East, and Central America. It may present with meningitis, meningoencephalitis, cranial neuropathies, myelopathy, radiculopathy, or stroke or as a brain abscess. The diagnosis is made by a positive culture or serologic test result for brucellosis in the CSF or blood. Treatment consists of combination antimicrobial therapy (such as ceftriaxone, rifampin, and doxycycline) for at least 6 months.

Parasitic Meningitis

Acute primary amebic meningoencephalitis caused by Naegleria, Balamuthia, and Acanthamoeba species is a fatal infection that clinically resembles bacterial meningitis. Freshwater exposure is a key historical clue. Examination of a fresh CSF sample can reveal motile trophozoites, but the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention should perform confirmatory testing by PCR. Treatment should include miltefosine.

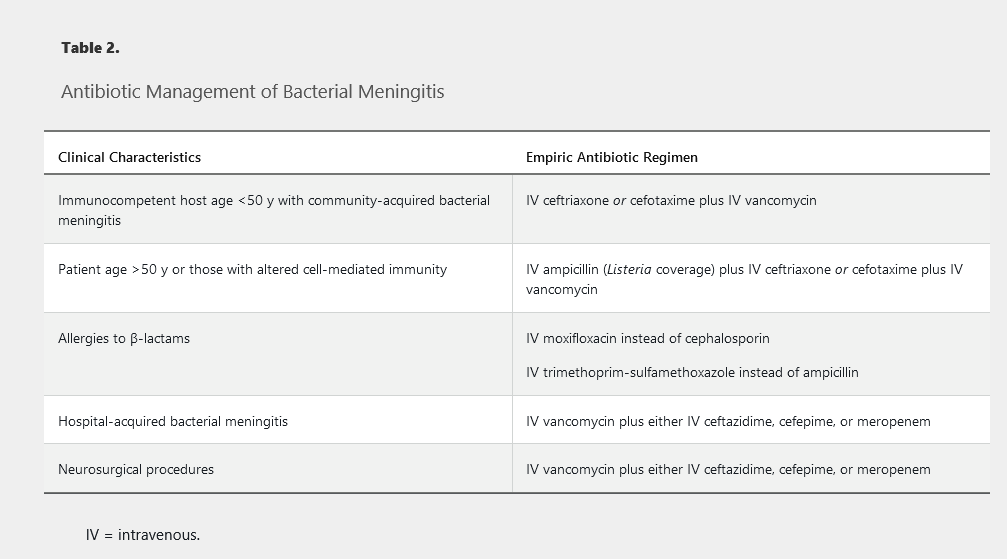

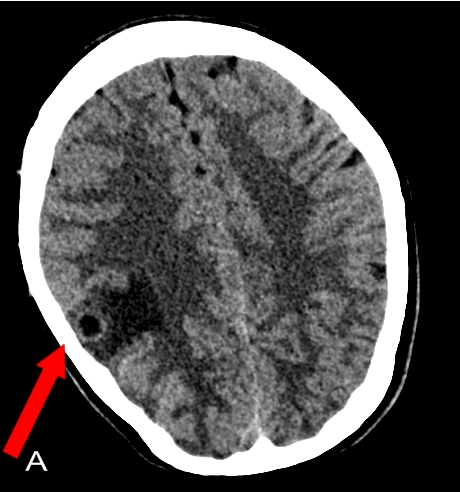

Helminth infections causing eosinophilic meningitis include Angiostrongylus cantonensis, Baylisascaris procyonis, Taenia solium (neurocysticercosis), Schistosoma species (schistosomiasis), and Gnathostoma. Neurocysticercosis is endemic in Mexico, South America, and Asia. It most commonly presents with seizures or hydrocephalus, and CT scan of the head shows multiple cysts or calcified lesions.

Noninfectious Causes

Medications such as NSAIDS, antibiotics, and intravenous immune globulin can occasionally cause aseptic meningitis. Meningeal involvement of leukemia, lymphoma, and metastatic carcinoma can also present as aseptic meningitis, with the CSF cytology showing atypical or immature cells and severe hypoglycorrhachia (<10 mg/dL [0.6 mmol/L]). Systemic lupus erythematosus, Behçet disease (recurrent oral and genital ulcers with iridocyclitis), Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome (uveomeningoencephalitis), and neurosarcoidosis can all present with aseptic meningitis. Finally, chemical meningitis can be seen after intrathecal injections, neurosurgical procedures, or spinal anesthesia.

Health Care–Associated Meningitis and Ventriculitis

Health care–associated meningitis and ventriculitis, or nosocomial meningitis, can occur after head trauma or a neurosurgical procedure (craniotomy, lumbar puncture) or secondary to a device infection (for example, CSF shunt or drain, intrathecal pump, deep brain stimulator). Normal or abnormal CSF cell count, glucose level, and protein level do not reliably confirm or rule out infection in these patients. Staphylococcus species and enteric gram-negative bacteria are the most common causes, but up to 50% of infections can have negative culture results. The use of β-D-glucan and galactomannan CSF assays may aid in the diagnosis of health care–related fungal ventriculitis and meningitis. Empiric antimicrobial therapy is outlined in Table 2 and should be accompanied by device removal if present.

An elevated CSF lactate level greater than 4 mg/dL, an elevated CSF procalcitonin level, or a combination of both, may be useful in the diagnosis of health care–associated bacterial ventriculitis and meningitis in culture-negative cases.

Intraventricular or intrathecal antimicrobial therapy should be considered for patients with health care–associated ventriculitis and meningitis in whom the infection responds poorly to systemic antimicrobial therapy alone.

Focal Central Nervous System Infections

Brain Abscesses

Brain abscesses can occur in immunocompetent or immunosuppressed persons and are most commonly seen in men. Predisposing conditions in immunocompetent patients can be seen in Table 3. Brain abscesses are most commonly caused by anaerobes, aerobic and microaerophilic streptococci, and Enterobacteriaceae. Initial empiric therapy is guided by the likely predisposing condition and is outlined in Table 4. Aspiration of the brain abscess for culture is preferred for definitive diagnosis; surgical or stereotactic drainage should be performed if the abscess is large (>2.5 cm). Antibiotic therapy should be given for 4 to 8 weeks with follow-up cranial imaging to ensure resolution of the infection.

Immunosuppressed patients (those with HIV or AIDS, patients undergoing solid organ or bone marrow transplantation) are at risk for development of brain abscesses from several opportunistic infections. See HIV/AIDS and Infections in Transplant Recipients for further discussion.

Cranial Abscess

Cranial epidural and subdural abscesses can arise from underlying osteomyelitis complicating paranasal sinusitis (Pott puffy tumor) or otitis media or after neurosurgical procedures or head trauma. Rarely, they may arise as a complication of bacterial meningitis. Cranial epidural abscesses are usually slow growing, presenting with subacute to chronic symptoms of headache, localized bone pain, and focal neurologic signs. In contrast, subdural empyema is a rapidly progressive infection with high mortality that represents a neurosurgical emergency. The CSF formula in both parameningeal infections shows neutrophilic pleocytosis and a very high protein level, frequently with negative Gram stain and culture results. Pathogen identification is best achieved by culture of the abscess obtained during surgical drainage.

Spinal Epidural Abscess

Spinal epidural abscess most commonly results from hematogenous dissemination, with S. aureus accounting for approximately 50% of infections; streptococcus and gram-negative bacilli such as Escherichia coli are also implicated. Predisposing factors for bacteremia include endocarditis, injection drug use, long-term intravenous catheters (hemodialysis catheters, central lines), and urinary tract infection. Spinal epidural abscess can also occur after neurosurgical procedures (spinal fusion, epidural catheter placement) or paraspinal injection. Patients usually develop localized pain at the site of infection that later radiates down the spine. MRI is the imaging modality of choice to identify location and extent of the abscess. All patients should undergo a baseline laboratory evaluation, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein. Blood cultures should be obtained before starting antibiotics. Empiric parenteral antimicrobial therapy should include coverage for Staphylococcus aureus (accounts for approximately 50% of infections), Streptococcus species, and gram-negative bacilli and may be narrowed based on culture results, if available Although the duration of antibiotic therapy lacks robust supporting data and must be determined on a case-by-case basis, at least 6 weeks of effective antimicrobial therapy is reasonable. Surgical drainage is indicated in patients with neurologic symptoms or signs (lower extremity weakness, numbness, bladder and bowel dysfunction). Follow-up MRI is not indicated unless the patient has persistent elevation of inflammatory markers, lack of clinical response, or new neurologic symptoms or signs. Tuberculosis (Pott disease) and brucellosis should be considered in patients with negative culture results and appropriate travel history and risk factors.

Encephalitis

Encephalitis is inflammation of the brain parenchyma. Possible encephalitis is defined by the presence of one major (altered consciousness for more than 24 hours) and two minor (fever, new-onset seizure, new-onset focal neurologic findings, CSF pleocytosis, and abnormal MRI or electroencephalographic findings) criteria from the International Encephalitis Consortium; probable or confirmed encephalitis requires one major and at least three minor criteria. The causative agent is unknown in 37% to 70% of infections, depending on whether viral PCR is used and autoimmune causes are investigated. The most common known causes are viral (herpes simplex virus types 1 and 6, varicella-zoster virus, and West Nile virus) and autoimmune diseases.

Viral Encephalitis

Herpes Simplex Encephalitis

HSV-1 is the most common cause of sporadic encephalitis in the United States, requiring prompt identification and treatment with intravenous acyclovir. Factors associated with an adverse outcome include older age, abnormal Glasgow coma scale, and delay in starting antiviral therapy. HSV-1 encephalitis presents with fever, seizures, altered mental status, and focal neurologic deficits with unilateral temporal lobe edema, hemorrhage, or enhancement on imaging. Bilateral temporal lobe findings in the insula or cingulate are less commonly seen. The CSF formula usually shows lymphocytic pleocytosis, an elevated protein level, and a normal glucose level. The diagnosis is confirmed by HSV PCR of the CSF (98% sensitivity, 94% specificity). However, false-negative results have been reported; if HSV is suspected, a repeat PCR should be obtained within 1 week while continuing acyclovir therapy. Therapy duration for HSV encephalitis should be 14 to 21 days. Electroencephalography can be helpful in identifying the degree of cerebral dysfunction and specific area of the brain involved and in detecting subclinical seizure activity.

Human herpesvirus 6 can cause severe encephalitis in transplant recipients. Cytomegalovirus can cause encephalitis with periventricular enhancement on imaging in immunosuppressed patients (those with AIDS or after transplantation). Diagnosis is by PCR of the CSF for cytomegalovirus, and treatment is parenteral ganciclovir. Cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus can cause meningoencephalitis in young, immunocompetent patients presenting with infectious mononucleosis syndromes.

Varicella-Zoster Virus Encephalitis

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is a commonly underdiagnosed, treatable cause of encephalitis in adults. VZV can present with vasculopathy with a stroke, encephalitis, meningitis, radiculopathy, or myelitis. Patients can present without a vesicular rash, so a PCR of the CSF or a serum-to-CSF anti-VZV IgG should be ordered in all patients with encephalitis. Treatment with intravenous acyclovir for 10 to 14 days is recommended.

Arboviruses

Arboviral CNS infections in the United States are most commonly seen in summer or fall and include West Nile (WNV), Eastern and Western equine encephalitis, St. Louis encephalitis, Powassan, and La Crosse viruses. WNV is the most common cause of epidemic viral encephalitis in the United States. WNV can cause meningitis, encephalitis, acute flaccid paralysis (similar to poliomyelitis), neuropathy, and retinopathy. Older patients and those who have undergone transplantation or are immunosuppressed have a higher risk of death. WNV affects the thalamus and the basal ganglia; patients present with facial or arm tremors, parkinsonism, and myoclonus. Hypodense lesions or enhancements may be seen in the thalamus, basal ganglia, and midbrain on MRI of the brain. Diagnosis is confirmed by a positive WNV IgM in the CSF or serum; treatment is supportive.

HIV encephalitis is the cause of HIV-associated dementia in later stages of the untreated illness; it can also present as CD8 encephalitis, consisting of perivascular inflammation resulting from infiltration of CD8+ lymphocytes, which may occur as part of an immune reconstitution syndrome, in some cases associated with viral escape (low levels of detectable HIV RNA in CSF).

Autoimmune Encephalitis

Autoimmune neurologic diseases can manifest as encephalitis, cerebellitis, dystonia, status epilepticus, cranial neuropathies, and myoclonus. Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis is most common; it was initially described as a paraneoplastic syndrome affecting young women with ovarian teratomas, but it can be associated with other tumors (sex cord stromal tumors, small cell lung cancer) or occur without a tumor. Young women (<35 years) often present after viral-like illness with behavioral changes, headaches, and fever followed by altered mental status, seizures, abnormal movements, and autonomic instability. Treatment includes intravenous glucocorticoids, intravenous immune globulin, tumor removal (if present), and, in some cases, plasmapheresis and rituximab.